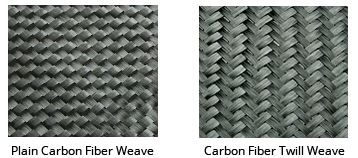

Carbon fiber is composed of carbon atoms bonded together to form a long chain. The fibers are extremely stiff, strong, and light, and are used in many processes to create excellent building materials. Carbon fiber material comes in a variety of "raw" building-blocks, including yarns, uni-directional, weaves, braids, and several others, which are in turn used to create carbon fiber composite parts.

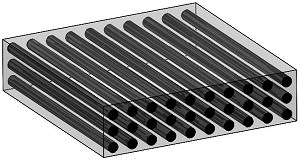

Within each of these categories are many sub-categories of further refinement. For example, different types of carbon fiber weaves result in different properties for the composite part, both in fabrication, as well as final product. In order to create a composite part, the carbon fibers, which are stiff in tension and compression, need a stable matrix to reside in and maintain their shape. Epoxy resin is an excellent plastic with good compressive and shear properties, and is often used to form this matrix, whereby the carbon fibers provide the reinforcement. Since the epoxy is low density, one is able to create a part that is light weight, but very strong. When fabricating a composite part, a multitude of different processes can be utilized, including wet-layup, vacuum bagging, resin transfer, matched tooling, insert molding, pultrusion, and many other methods. In addition, the selection of the resin allows tailoring for specific properties.

Carbon fibers reinforcing a stable matrix of epoxy

Carbon fibers reinforcing a stable matrix of epoxy

Strength, Stiffness, and Comparisons With Other Materials

Carbon fiber is extremely strong. It is typical in engineering to measure the benefit of a material in terms of strength to weight ratio and stiffness to weight ratio, particularly in structural design, where added weight may translate into increased lifecycle costs or unsatisfactory performance. The stiffness of a material is measured by its modulus of elasticity. The modulus of carbon fiber is typically 33 msi (228 GPa) and its ultimate tensile strength is typically 500 ksi (3.5 Gpa). High stiffness and strength carbon fiber materials are also available through specialized heat treatment processes with much higher values. Compare this with 2024-T3 Aluminum, which has a modulus of only 10 msi and ultimate tensile strength of 65 ksi, and 4130 Steel, which has a modulus of 30 msi and ultimate tensile strength of 125 ksi.

Steel will permanently deform at a stress level below its ultimate tensile strength. The stress level at which this occurs is called the yield strength. Carbon fiber, on the other hand, will not permanently deform below its ultimate tensile strength, so it effectively has no yield strength.

As an example, a plain-weave carbon fiber reinforced laminate has an elastic modulus of approximately 6 msi and a volumetric density of about 83 lbs/ft3. Thus the stiffness to weight for this material is 107 ft. By comparison, the density of aluminum is 169 lbs/ft3, which yields a stiffness to weight of 8.5 x 106 ft, and the density of 4130 steel is 489 lbs/ft3, which yields a stiffness to weight of 8.8 x 106 ft. Hence even a basic plain-weave carbon fiber panel has a stiffness to weight ratio 18% greater than aluminum and 14% greater than steel. The utilization of prepreg, and in particular high modulus and ultra high modulus carbon fiber prepregs, yields substantially higher stiffness to weight ratios. For example, a panel comprising a 0/90 layup of standard modulus prepreg carbon fiber will have a bending modulus of about 8 msi, or about 30% more rigid than non-prepreg options. For very demanding applications where maximum stiffness is required, 110 msi ultra high modulus carbon fiber can be used. This specialized pitch-based carbon fiber has a bending stiffness over 3 times that of a standard modulus prepreg panel (about 25 msi). When one considers the possibility of customized carbon fiber panel stiffness through strategic laminate placement, a panel (or other cross-section, such as a tube) can be fabricated with bending stiffness on the order of 50 msi.

Testing performed by Dragonplate has demonstrated all zero-degree oriented uni-directional ultra high modulus coupon samples to have tensile stiffness in excess of 75 msi, or over twice the stiffness of steel, yet still only half the weight of aluminum. Using the aforementioned comparison, the stiffness to weight ratio of this material is then over 10 times that of either steel or aluminum. When one includes the potentially massive increases in both strength to weight and stiffness to weight ratios possible when these materials are paired with lightweight honeycomb and foam cores, is it obvious the impact advanced carbon fiber composites can make on a wide variety of applications.

What is a Composite Sandwich Structure?

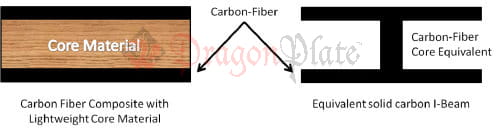

A composite sandwich combines the superior strength and stiffness properties of carbon-fiber with a lower density core material. In the case of Dragonplate sandwich sheets, the carbon-fiber creates a thin laminate skin over a foam, honeycomb, balsa, or birch plywood core. By strategically combining these materials, one is able to create a final product with much higher stiffness to weight ratio than with either alone. For applications where weight is critical, carbon-fiber sandwich sheets may be the right fit.

A composite sandwich structure is mechanically equivalent to a homogeneous I-Beam construction in bending.

Figure 1: Diagram showing carbon-fiber composite sandwich and equivalent I-Beam

Figure 1: Diagram showing carbon-fiber composite sandwich and equivalent I-Beam

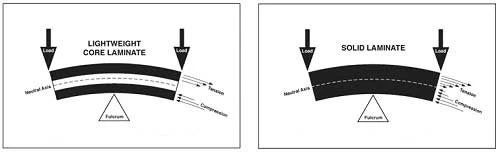

Referring to the picture of the sandwich structure, at the center of the beam (assuming symmetry) lies the neutral axis, which is where the internal axial stress equals zero. Moving from bottom to top in the diagram, the internal stresses switch from compressive to tensile. Bending stiffness is proportional to the cross-sectional moment of inertia, as well as the material modulus of elasticity. Thus for maximum bending stiffness, one should place an extremely stiff material as far from the neutral axis as possible. By placing carbon fiber furthest from the neutral axis, and filling the remaining volume with a lower density material, the result is a composite sandwich material with high stiffness to weight ratio.

Figure 2: Comparison of internal stress distribution for solid laminate and sandwich construction in bending.

Figure 2: Comparison of internal stress distribution for solid laminate and sandwich construction in bending.

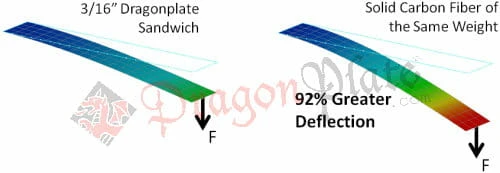

FEA analyses comparing sandwich laminate with solid carbon fiber are shown below. These calculations show the deflections of a cantilever beam with a load placed at the end. In the figure, 3/16" birch plywood core laminate is shown next to a solid carbon fiber layup of equal weight. Due to the reduced thickness of the solid carbon beam, it deflects significantly more than the equivalent beam made using a core material. As the thickness increases, this disparity becomes even greater due to the large weight savings from the core. In a similar light, one can replace a solid carbon structure with a lighter one of equivalent strength and stiffness made from any of the core options previously mentioned.

Figure 3: Finite element analysis comparison between Dragonplate sandwich laminate and solid carbon fiber

Figure 3: Finite element analysis comparison between Dragonplate sandwich laminate and solid carbon fiber

When utilizing the various cores, each one has strengths and weaknesses. Typically the driving factors are compressive and shear strength of the core. For example, if high compressive strength (and hence high crush resistance) is required, then the core will most likely need to be higher density (high density foam or birch plywood are good options here). If, however, one needs the absolute lowest weight composite possible, and the stresses are relatively small (i.e. low load, high stiffness application), then an extremely lightweight foam or honeycomb core may be the best selection. Some cores offer better moisture resistance (closed cell foam), some better machinability (plywood), and others high compressive strength to weight ratio (balsa). It is up to the engineer to understand the tradeoffs during the design process in order to maximum the potential of cored composites. That said, for weight critical applications, there is often no other option that even comes close to the potential strength and stiffness to weight ratios of carbon fiber sandwich core laminates.

COMPARISON CRITERIA | |||||

| PRODUCTS | Stiffness to Weight | Toughness | Crushability | Moisture Resistance | Sound Absorbency |

| Solid Carbon Fiber | GOOD | BETTER | BEST | BEST | POOR |

| High Modulus Solid Carbon Fiber | BETTER | GOOD | BETTER | BEST | POOR |

| Birch Core | BETTER | BEST | BEST | GOOD | POOR |

| Balsa Core | BETTER | GOOD | BETTER | POOR | GOOD |

| Nomex Honeycomb Core | BEST | GOOD | BETTER | BETTER | BEST |

| Depron Foam Core | BETTER | POOR | POOR | BETTER | BETTER |

| Airex Foam Core | BEST | GOOD | GOOD | BETTER | BETTER |

| Divinycell Foam Core | BETTER | BETTER | BETTER | BETTER | GOOD |

| Last-A-Foam Core | BETTER | BETTER | BETTER | BETTER | BETTER |

Pros and Cons

Carbon fiber reinforced composites have several highly desirable traits that can be exploited in the design of advanced materials and systems. The two most common uses for carbon fiber are in applications where high strength to weight and high stiffness to weight are desirable. These include aerospace, military structures, robotics, wind turbines, manufacturing fixtures, sports equipment, and many others. High toughness can be accomplished when combined with other materials. Certain applications also exploit carbon fiber's electrical conductivity, as well as high thermal conductivity in the case of specialized carbon fiber. Finally, in addition to the basic mechanical properties, carbon fiber creates a unique and beautiful surface finish.

Although carbon fiber has many significant benefits over other materials, there are also tradeoffs one must weigh against. First, solid carbon fiber will not yield. Under load carbon fiber bends but will not remain permanently deformed. Instead, once the ultimate strength of the material is exceeded, carbon fiber will fail suddenly and catastrophically. In the design process it is critical that the engineer understand and account for this behavior, particularly in terms of design safety factors. Carbon fiber composites are also significantly more expensive than traditional materials. Working with carbon fiber requires a high skill level and many intricate processes to produce high quality building materials (for example, solid carbon sheets, carbon fiber sandwich laminates, carbon tubes, etc). Very high skill level and specialized tooling and machinery are required to create custom-fabricated, highly optimized parts and assemblies.

Carbon Fiber vs. Metals

When designing composite parts, one cannot simply compare properties of carbon fiber versus steel, aluminum, or plastic, since these materials are in general homogeneous (properties are the same at all points in the part), and have isotropic properties throughout (properties are the same along all axes). By comparison, in a carbon fiber part the strength resides along the axis of the fibers, and thus fiber properties and orientation greatly impact mechanical properties. Carbon fiber parts are in general neither homogeneous nor isotropic.

The properties of a carbon fiber part are close to that of steel and the weight is close to that of plastic. Thus the strength to weight ratio (as well as stiffness to weight ratio) of a carbon fiber part is much higher than either steel or plastic. The specific details depend on the matter of construction of the part and the application. For instance, a foam-core sandwich has extremely high strength to weight ratio in bending, but not necessarily in compression or crush. In addition, the loading and boundary conditions for any components are unique to the structure within which they reside. Thus it is impossible for us to provide the thickness of carbon fiber plate that would replace the steel plate in your application. It is the customer's responsibility to determine the safety and suitability of any Dragonplate product for a specific purpose. This is accomplished through engineering analysis and experimental validation.

கருத்துகள் இல்லை:

கருத்துரையிடுக